Eisenmenger’s Syndrome

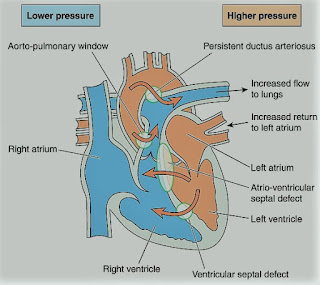

-A rare syndrome of pulmonary

hypertension associated with a reversed or bidirectional cardiac shunt,

occurring through a large communication between the left and right sides of the

heart. The defect may be interventricular, interatrial, or aortopulmonary.

-The development of Eisenmenger’s

syndrome, from the initial left to right shunt, is usually a gradual process.

Contributory factors to pulmonary hypertension are hypoxia, high pulmonary

blood flow, and high left atrial pressure.

-Irreversible structural changes

take place in the small vessels, causing pulmonary vascular obstruction and a

reduction in the size of the capillary bed. The pulmonary artery pressure is

the same as or sometimes exceeds, the systemic arterial pressure.

-The incidence of this syndrome is

decreasing because of the more vigorous approach to diagnosis and treatment of

congenital heart disease in childhood.

Preoperative Findings:

1. Presenting symptoms include dyspnea,

tiredness, episodes of cyanosis, syncope, or chest pain. Hemoptysis may occur.

2. The direction of the shunt, and

hence the presence or absence of cyanosis, depends on several factors.

These include hypoxemia, pulmonary and systemic pressure differences, and intravascular volume. It can also be affected by certain drugs.

3. Sleep studies have shown that

there is a nocturnal deterioration in arterial oxygen saturation, which seems

to be related to ventilation/perfusion distribution abnormalities occurring in

the supine position.

4. Chest X-ray shows right

ventricular hypertrophy, and ECG indicates varying degrees of right ventricular

hypertrophy and strain.

5. Complications include thrombosis

secondary to polycythemia, air embolus, bacterial endocarditis, gout, cholelithiasis,

and hypertrophic osteoarthropathy. A cerebral abscess may occur secondary to clot

embolism.

Anesthetic Problems:

1. Reductions in systemic arterial

pressure by myocardial depression or loss of sympathetic tone are potentially

dangerous. Reversal of the shunt may occur, and sudden death has been reported.

Hypovolemia and dehydration are

poorly tolerated. Syntocinon may cause a dramatic reduction in SpO2

secondary to vasodilatation.

2. Sinus tachycardia results from

exercise or emotion, and episodes of SVT are common after the age of 30. The

onset of atrial fibrillation is associated with a sudden deterioration in the

condition of the patient.

3. General anesthesia tends to be

favored since the reduction in systemic vascular resistance associated with

regional blockade increases the shunt. However, successful use of epidural anesthesia

for bilateral inguinal herniorrhaphy, and Cesarean section, have been reported.

4. Pregnancy is contraindicated

because it carries considerable risks. Recent maternal mortality rates of 40%

have been reported. A cesarean section may increase it to over 60%. Termination

of pregnancy is usually recommended in the first trimester but is still

associated with a mortality of 7%.

5. Patients are at risk from

paradoxical air or clot embolism, and infective endocarditis.

Anesthetic Management:

1. Understanding the

pathophysiology of the complex is essential, and both pregnancy and non-cardiac

surgery require a multidisciplinary approach.

2. Maintenance of an adequate

circulating blood volume is important. Myocardial depressants and peripheral

vasodilators should be used with caution. Bradycardia must be prevented. If

regional anesthesia is used, the block should be instituted with caution, and

hypovolemia avoided.

3. It is unclear whether

oxygen can cause pulmonary vasodilatation. Although the pulmonary vascular

resistance was believed to be fixed in pulmonary hypertension, a high oxygen

concentration has been shown to reduce it during cesarean section.

4. Maintenance of systemic vascular

resistance is critical. The use of a norepinephrine infusion before induction

has been described. Alpha-adrenergic vasopressors, such as methoxamine or

phenylephrine, have also been used for the treatment of hypotension on

induction of anesthesia.

5. Pulmonary ventilation should be

performed with low inflation pressures and early tracheal extubation is

advised, because of the deleterious effects of IPPV.

6. Air must be completely eliminated

from all intravenous lines and the epidural space should be located with loss

of resistance to saline, not to air.

7. Antibiotic prophylaxis against bacterial

endocarditis.

8. Low-dose heparin may reduce the

risk of emboli.

9. Patients are usually advised

against pregnancy. If anesthesia is required either for termination of

pregnancy or operative delivery, intensive cardiac care is indicated. It has

been suggested that those reaching the end of the second trimester should be

admitted to the hospital until delivery and given heparin 20000-40000 units daily and

oxygen therapy. Successful epidural anesthesia has been reported for cesarean

section.