Treacher Collins Syndrome:

-A craniofacial defect associated with developmental anomalies of the first arch.

-Abnormalities vary from minimal, to complete syndrome.

-The syndrome is named after Edward Treacher Collins, an English surgeon and ophthalmologist, who described its essential traits in 1900.

-Patients may require anesthesia for maneuvers to improve upper airway obstruction temporarily, or for correction of some of the congenital defects.

-Airway obstruction and a requirement for multiple operations increase the need for tracheostomy.

Etiology:

-It is due to mutations in TCOF1, POLR1C, or POLR1D genes. TCOF1 gene mutations are the most common cause of the disorder, accounting for 81 to 93% of all cases. POLR1C and POLR1D gene mutations cause an additional 2% of cases. In individuals without an identified mutation in one of these genes, the genetic cause of the condition is unknown.

Preoperative Abnormalities:

1. Features may include mandibular and malar hypoplasia, antimongoloid palpebral fissure, macrostomia, irregular maloccluded teeth, microphthalmia, lower lid defects, cleft palate, high arched palate, macroglossia, and auricular deformities.

2. Associated abnormalities include mental retardation, deafness, dwarfism, cardiac defects, choanal atresia, and skeletal deformities.

3. Chronic upper respiratory tract obstruction and obstructive sleep apnea, which can lead to growth retardation and/or cor-pulmonale.

Anesthetic Problems:

1. Upper airway obstruction: in neonates, this may require urgent temporary maneuvers, such as stitching the tongue to the lower lip

2. Excess secretions: may impede induction of anesthesia

3. Inhalational induction: may be difficult

4. Difficult tracheal intubation

5. Obstructive sleep apnea may occur postoperatively

6. Pulmonary edema

Intraoperative Management:

Recommendations:

1-Monitoring by pulse oximetry, to detect airway obstruction, is crucial.

2-Avoid respiratory depressant drugs, both for premedication and postoperatively

3-Use drying agents

4-Never give muscle relaxant until the airway has been secured.

Airway Management:

-Several methods have been proposed to overcome the problem of difficult intubation, some in the awake patient and some under general anesthesia:

a) In Awake Patients:

1-Awake intubation or awake direct laryngoscopy to visualize the vocal cords.

2-Direct laryngoscopy, with the patient in the sitting position, and using a 5-G feeding tube taped to the side of the laryngoscope to give oxygen.

3-The Augustine guide (Figure 1): can be used for nasotracheal intubation in an awake, sedated patient.

|

| Figure 1: Augustine guide |

4-Fibreoptic bronchoscope or Tracheostomy under local anesthesia:

In small infants, the ‘tube over bronchoscope’ technique is not always possible because of the small size of the tube, therefore a Seldinger-type approach may be necessary:

-After the administration of atropine, ketamine IM, and topical lidocaine, a fibreoptic bronchoscope (OD 3.6mm, L 60 cm, and suction channel 1.2 mm) was passed through one nostril.

-The tongue was held forward with Magill forceps, until the vocal cords were seen, but not entered, because of the risk of total obstruction.

-Under direct vision, a Teflon-coated guidewire with a flexible tip was passed via the suction channel into the trachea.

-The bronchoscope was carefully removed leaving the wire in place, and an ID 3mm nasotracheal tube was then passed over it into the trachea.

Pediatric bronchoscopes of 2.5 mm diameter are now available, but their very fineness makes them less easy to handle than the 4-mm bronchoscopes).

b) In Anesthetized Patients:

1-Jackson anterior commissure laryngoscope (Figure 2):

-The head is elevated above the shoulders, with flexion of the lower cervical vertebrae and extension at the atlanto-occipital joint. The laryngoscope is introduced into the right side of the mouth. Only the tip is directed towards the midline, the proximal end remaining laterally so that a further 30 degrees of anterior angulation can be obtained.

-The narrow, closed blade prevents the tongue from falling in and obscuring the view of the larynx. When visualized, the epiglottis is elevated, and the larynx is entered. Intubation is then achieved by passing a lubricated tube, without its adaptor, down the laryngoscope. It is held in place with alligator forceps whilst the laryngoscope is withdrawn.

|

| Figure 2: Jackson anterior commissure laryngoscope |

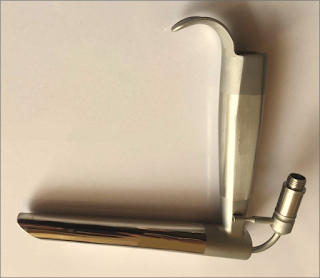

2-The Bullard intubating laryngoscope (Figure 3):

-It can be used to achieve nasotracheal intubation.

|

| Figure 3: Bullard intubating laryngoscope |

3-Tactile nasal intubation:

-Inhalational induction with sevoflurane, and the tongue is pulled downwards and forwards. The tube is initially used as a nasal airway, whilst the index and middle finger are used to palpate the epiglottis, through which the tube is then passed.

4-Laryngeal mask airway:

-Inserted under propofol anesthesia and can be used as a conduit for the passage of a fibreoptic bronchoscope.

5-The use of an assistant to pull out the tongue with Magill forceps, and at the same time to apply cricoid pressure, to assist laryngoscopy.

Postoperative Management:

-The tracheal tube should remain in place until the patient is fully awake.

-Patients should be nursed in a high-dependency area postoperatively. The combination of sleep apnea and drugs with CNS-depressant effects may make them particularly susceptible to respiratory arrest.

Read more ☛ Pierre Robin Syndrome