➧ Despite the frequent use of tracheal intubation (TI) for both short-term events like surgery or for long-term ventilatory support, traumatic complications from TI still occur.

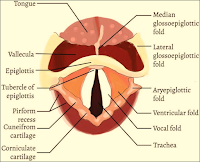

➧ Both the upper and lower airways are at risk of injury. The upper airway includes the naso- and oro-pharynx and extends to the level of the vocal cords. The lower airway lies distal to the vocal cords.

1-Lips injury:

➧ Frequently the right lower lip is caught between the laryngoscope blade and the lower teeth.

➧ It can also occur when the endotracheal tube (ETT) is placed or when a hard plastic oral airway is placed.

➧ There is frequently soft tissue injury to the lip, but serious consequences are rare.

2-Dental injury:

➧ The upper incisors are usually involved. Identified risk factors include preexisting poor dentition and one or more indicators of difficult laryngoscopy and intubation.

➧ A protective plastic shield placed over the upper teeth may limit the potential for damage to teeth.

3-Tongue injury:

➧ Prolonged compression by an ETT, an oral airway, or both may impair circulation, leading to ischemia and poor venous drainage, which then leads to macroglossia.

➧ Obstruction of the submandibular duct by an ETT may lead to massive tongue swelling.

➧ Compression injury to the lingual n. during difficult intubation has been reported with a one-month loss of tongue sensation.

4-Uvular injury:

➧ Injury to the uvula is a rare complication of TI and is usually associated with mechanical interference with the blood supply to the uvula during intubation.

➧ Common causes of such interference include compression caused by excessive length of the ETT leading to direct pressure, blind pharyngeal suction with a hard suction catheter, and entrapment of the uvula between the ETT and oral airway.

➧ This condition causes sore throat, difficulty in breathing, painful swallowing, and foreign body sensation in the throat.

➧ Treatment of patients with steroids and antibiotics is successful, with complete healing in 2 weeks.

5-Nasal injury:

➧ Nasal intubations in particular are associated with mucosal tears or lacerations that may result in significant epistaxis.

➧ The use of nasal decongestants/vasoconstrictors, lubrication of the ETT, and warming of the tube before nasal intubation may reduce the risk of epistaxis.

➧ Once the nasotracheal tube is in place, it is important to position the tube in such a way as to prevent distortion of the nares, which can lead to local ischemia, followed by necrosis.

➧ Blind nasal intubation also increases the risk of oropharyngeal and laryngeal injury, as does oral intubation with a protruding stylet.

➧ Pharyngeal injury can progress into retropharyngeal infections or mediastinitis, and positive pressure ventilation may produce subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum, and pneumothorax.

6-Temporal-Mandibular Joint injury:

➧ This joint can be dislocated during TI.

7-Cervical Spine injury:

➧ Risk factors for spinal injury include head and neck trauma, cervical osteoporosis, atlantoaxial instability as seen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and Down's syndrome, and lytic bone lesions.

➧ Immobilization of the head and neck will prevent most spine injuries regardless of the route or method of intubation.

8-Pharyngeal and Esophageal injury:

➧ Venous drainage from the pharynx may be impaired by the mechanical presence of the tracheal tube and result in pharyngolaryngeal edema.

➧ Both pharyngeal and esophageal perforations can occur after a difficult TI and in patients older than 60 y.

9-Laryngeal injury:

a) Vocal Cord Paralysis:

➧ Vocal cord paralysis is attributed to nerve injury or mechanical injury.

➧ It may be unilateral or bilateral, bilateral injury is riskier and frequently requires emergency reintubation or tracheotomy.

➧ The mechanism may be related to inflation of the ETT cuff at the level of the subglottic larynx rather than at the correct location in the trachea where an anterior branch of the recurrent laryngeal n. enters between the cricoid and the thyroid cartilage, providing innervation to the intrinsic muscles of the larynx.

➧ An inflated cuff at this location can compress the nerve between the cuff and the overlying thyroid cartilage, causing injury.

➧ This can be exacerbated when N₂O is used as part of the general anesthesia, as it diffuses rapidly into the cuff, increasing cuff pressure (Pcuff) and risk for injury.

➧ Vocal cord immobility may also be caused by pseudolaryngeal paralysis which can be associated with cricoarytenoid dislocation, arytenoid fusion, and posterior glottic stenosis.

➧ Interarytenoid fibrous adhesion can occur after intubation and is frequently confused with bilateral vocal cord paralysis.

➧ Measures to decrease the risk for recurrent laryngeal n. injury include:

-Use of a low-pressure, high-volume ETT cuff

-Avoidance of larger than necessary ETTs

-Avoidance of overinflation of the ETT cuff

-Prevention of excessive tube migration during anesthesia

➧ Vocal cord paralysis is usually associated with spontaneous recovery.

b) Arytenoid Cartilage Dislocation:

➧ The arytenoid cartilage can be dislocated from the cricoarytenoid joint due to the pressure of the tip of the tracheal tube as it is placed through the vocal cords.

➧ This rare complication can occur with routine elective intubation and most often during traumatic intubation, intubations in which the patient is not relaxed and is struggling or coughing during tube placement and with the use of certain airway devices such as the McCoy laryngoscope or the lighted stylet (lightwand).

➧ Acutely dislocated arytenoid cartilage can be reduced using rigid bronchoscopy.

➧ If the dislocation is not reduced, chronic hoarseness and vocal cord dysfunction often result.

c) Hematoma and Granuloma formation:

➧ Hematoma formation on the vocal cords has been noted after routine TI and usually resolves without sequelae.

➧ Occasionally scarring of the injured area occurs, resulting in a chronically hoarse voice.

➧ Granulomas can also form after hematomas on the vocal cords resulting from TI.

➧ Granuloma formation after intubation has been described as occurring with an incidence of 1:800 to 1:20000 in adults.

➧ The most common site is the vocal process of the arytenoids because this structure comes into close contact with the ETT.

➧ The degree of injury increases with increasing tube size and duration of intubation.

10-Tracheal injury:

➧ Tracheal laceration as a result of intubation was first reported in 1977.

➧ Factors related to this type of injury include:

-Overinflation of the ETT cuff

-Multiple intubation attempts

-Use of stylets

-Malpositioning of the tube tip

-Tube repositioning without cuff deflation

-Inadequate tube size

-Vigorous coughing

-N₂O in the cuff

-Traumatic intubation

-Emergency intubation

-Anesthesia protocol

-An oversized tube

-Long duration of intubation.

➧ The risk is also greater in patients with:

-Tracheal distortion caused by neoplasm or large lymph nodes

-Weakness in the membranous trachea (seen in women or the elderly)

-Chronic obstructive lung disease

-Corticosteriod therapy.

➧ The most common site for tracheal rupture is the junction of the cartilage and posterior membrane on the right side and the length of the tear often corresponds to the length of the cuff on the ETT.

➧ Translaryngeal ETTs can cause circumferential stenosis or malacia at the cuff site. Tracheal stenosis can develop after even a brief (<24 h.) TI.

➧ The incidence of injury at the cuff site was likely higher in the era of high-pressure, low-volume cuffs and has certainly declined with the use of low-pressure, high-volume cuffs since the 1970s.

➧ The newer cuffs, however, can easily be overinflated, exceeding the tracheal mucosal capillary perfusion pressure of 20-30 mmHg, and resulting in local tissue ischemia, which is directly proportional to the tracheal tube Pcuff. (

Methods to stabilize ETT intracuff pressure)

➧ At a Pcuff of 30 cmH₂O, the tracheal mucosal blood flow becomes partially obstructed, and at a pressure of 45 cmH₂O, the obstruction becomes total, leading to tracheal mucosal damage and subsequent complications.

➧ These lesions heal with either fibrous stenosis or loss of cartilaginous support and ensuing malacia.

Diagnosis:

➧ The clinical manifestations of laryngeal and tracheal injury can range from mild hoarseness to severe stridor.

➧ Patients also may present with other non-specific symptoms such as exertional dyspnea and positional wheezing.

➧ The airway is typically narrowed to less than 8 mm before exertional dyspnea is present.

➧ Once the lumen is less than 5 mm, symptoms of dyspnea and stridor may present at rest.

➧ Due to the dramatic loss of airway diameter before the development of symptoms, up to 54% of patients with tracheal stenosis can present in respiratory distress.

Treatment:

➧ Treatment of airway injury from prolonged intubation varies with the cause of injury but may include:

-Bronchoscopy and dilation

-Laser treatments of granulomas and webs

-Resection of stenotic tracheal rings

-Splitting the cicoid gland (cartilage).