Categories

- Airway

- Anesthesia machine

- Anesthetic drugs

- CNS diseases

- Complications in anesthesia

- Congenital cardiovascular diseases

- Endocine Emergencies

- Fluid & Electrolyte disturbances

- GIT diseases

- ICU

- Inborn errors of metabolism

- Infections

- Monitoring

- Neuropsychiatric diseases

- Nutritional

- Obstetric anesthesia

- Ophthalmic anesthesia

- Otorhinolaryngology

- Pediatric anesthesia

- Plastic

- Regional anesthesia

- Renal diseases

- Research

- Respiratory diseases

- Skin & Musculoskeletal diseases

- Thoracic surgery

Tachycardia during Anesthesia

Bradycardia during Anesthesia

Bradycardia during Anesthesia

Definition:

-Pulse rate less than 60 beats/min. in adults-Pulse rate less than 80 beats/min. in infants

-Pulse rate less than 100 beats/min. in neonates

Causes and Management:

1-Hypoxia:

-Late response is bradycardiaTreatment:

-Of the cause, Oxygenation, Anticholinergics

2-Drug induced:

-High-concentration volatile anesthetics, Opioids, Succinylcholine, Anticholinesterases (Neostigmine), Low dose atropine (Benzold-Jarisch reflex, paradoxical bradycardia), β-blockers, DigoxinTreatment:

-Decrease concentration of volatile anesthesia, Anticholinergics

3-Vagal stimulation:

- Airway instrumentation, Visceral traction, Extraocular muscle traction, Anal dilatation, Cervical dilatationTreatment:

-Stop traction or dilatation, Anticholinergics

4-Spinal anesthesia:

-High spinal anesthesia affecting T1-T4 (Cardiac accelerator fibers)Treatment:

-Support circulation, Anticholinergics, Ephedrine (if associated with hypotension)

5-Ischemic heart disease:

-Ischemic changes affecting the conducting systemTreatment:

-Anticholinergics if indicated

6-Endocrine disease:

-HypothyroidismTreatment:

-Anticholinergics

7-Metabolic:

-HyperkalemiaTreatment:

-Correction of potassium level, Anticholinergics

8-Neurological:

-Cushing’s reflex due to increased ICPTreatment:

-Of the cause, Anticholinergics if indicated

9-Cardiovascular fitness:

-Trained athlete (High resting vagal tone, Large stroke volume)N.B.: Anticholinergic drugs (Atropine, Glycopyrrolate, Hyoscine)

Esophageal Achalasia

Esophageal Achalasia

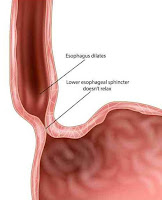

Definition:

A chronic, progressive motor

disorder of the esophagus associated with degenerative changes in the myenteric

ganglia and vagal nuclei.

Components:

There are three components:

1-Failure of the lower esophageal

sphincter to relax, with an increased resting sphincter pressure, which

together results in a functional obstruction

2-Absence of sequential peristalsis in

response to a bolus of food

3-Dilated, contorted esophagus

Pathophysiology and Management:

-Degeneration of the myenteric

plexus and decreased nitric oxide synthesis may be the problem.

-Overspill may produce

bronchopulmonary complications, and 5–10% of patients ultimately develop

carcinoma of the esophagus.

-Nitrates and calcium channel

blockers given before meals sometimes produce symptomatic improvement, but the

mainstays of treatment are esophageal dilatation and surgical myotomy.

-Open surgery has been mostly

replaced by laparoscopic myotomy and fundoplication.

-For elderly patients, an endoscopic

injection of botulinum toxin can give relief for several months without the

risk of surgery.

Preoperative Findings:

1. Symptoms include; dysphagia,

retrosternal pain, regurgitation, and weight loss. In young people, the

condition may be misdiagnosed as anorexia nervosa or asthma.

2. Respiratory complications, which

may be attributed to asthma or chronic bronchitis, are secondary to the overspill

of undigested material.

3. Nocturnal coughing occurs in 30%,

and bronchopulmonary complications in 10% of patients.

4. The aspiration of larger volumes

may result in lobar collapse, bronchiectasis, or lung abscess.

5. Rarely, it may present with a

cervical mass and acute upper respiratory tract obstruction, necessitating

urgent intervention.

6. There is an increased risk of esophageal

carcinoma.

7. Diagnosis can be made on barium

swallow, manometric studies, and endoscopy. Occasionally, acute dilatation may

be seen on CXR, in which case, abnormal flow–volume curves will indicate

variable intrathoracic tracheal obstruction.

Anesthetic Problems:

1. A predisposition to regurgitation

and pulmonary aspiration in the perioperative period.

2. Passage of the tracheal tube past

the dilated esophagus can be achieved with difficulty.

3. During recovery from anesthesia, neck

swelling, and venous engorgement can be precipitated by coughing or straining.

Acute thoracic inlet obstruction with stridor, deep cyanosis of the

face, and hypotension can occur.

4. Upper airway obstruction or

respiratory failure, particularly in the elderly. Rarely, an acute dilatation

of the esophagus results in total airway obstruction.

5. Acute respiratory failure can

occur after surgery.

6. The opening pressure of the

cricopharyngeus muscle from above is much lower than that from below, therefore

progressive dilatation of the upper esophagus may occur, particularly in

association with mask ventilation or IPPV.

7. An increased intrathoracic pressure

produced by a Valsalva maneuver forces air from the thoracic into the cervical esophagus.

Occasionally, death can occur.

8. If acute airway obstruction is

present, sudden decompression of the esophagus may cause the pharynx to flood

with food and fluid, resulting in aspiration.

Anesthetic Management:

1. If anesthesia is required,

precautions must be taken to reduce the risk of aspiration of gastric contents.

The dilated esophagus must be emptied and decompressed. This needs a period of

prolonged starvation, possibly with washouts of the esophagus.

2. A rapid sequence induction should

be undertaken with awake tracheal extubation, the patient should be nursed in

the lateral position during recovery.

3. Sublingual nifedipine 10–20 mg

has been shown to reduce the basal sphincter pressure after 10 min and the

effect lasts for up to 40 min.

4. Management of acute upper airway

obstruction secondary to tracheal compression has been reported using the

following methods:

a) Sublingual glyceryl nitrate.

b) Passage of a naso-esophageal

tube.

c) Transcutaneous needle puncture.

d) Tracheal intubation.

e) Rigid esophagoscopy.

f ) Emergency tracheostomy.

g) Cricopharyngeus myotomy.

5. Treatment can be either surgical or medical. For the elderly and less fit patients, pneumatic dilatation, or endoscopic injection of botulinum toxin, may be appropriate. Heller myotomy and partial fundoplication can be performed either as an open or a laparoscopic procedure.

Followers

Featured Post

Popular Posts

-

Accidental Total Spinal Anesthesia Definition: ➧ A syndrome of the central neurological blockade. ➧ It occurs when a vol...

-

Airway Blocks 1-Superior laryngeal n. block: Block of the superior laryngeal nerve can provide anesthesia of the larynx from the epiglottis ...

-

Awareness during Anesthesia Groups at risk for awareness: Awareness is due to too light plane of anesthesia. It is more likely where mus...

-

Anesthetic Considerations for Patients with Liver Disease Preoperative: 1. Assess the Degree of hepatic impairment, Severity, and Hepati...

-

Failed Spinal Anesthesia Introduction: ➧ Spinal (intrathecal) anesthesia is one of the most reliable regional block methods: the needle...

-

Laryngeal Mask Airway (LMA) 1-The LMA-Classic™: -It is a reusable LMA™ airway for general anesthesia. -The LMA-Classic™ is available in...

-

Dexmedetomidine Mechanism of Action: -It is an imidazole derivative and is a specific alpha-2 adrenoceptor agonist that acts via post-sy...

-

Fat Embolism Syndrome (FES) ➧ Fat embolism can be difficult to diagnose. It most often follows a closed fracture of a long bone but there...

-

Methods to stabilize ETT intracuff pressure -The use of N₂O, which is well-known to diffuse into ETT cuffs, and the lack of frequent cont...

-

IV Fluids A) Crystalloid solutions (< 30 000 Dalton): 1-Hypotonic solutions: - D 5 W, ½ NS, D5 ¼ NS, D5 ½ NS. 2-Isotonic solutio...